Audio Processing Attack Delay Sustain Release

Retrieved 14 January 2012. Bush, John. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

'Simian Mobile Disco: Attack Decay Sustain Release'. November 2007.

(keyboard notes)Right now, it has a very sharp attack,it sustains at maximum level, so the decay doesn't reallycome into play, and a very fast release.(keyboard note)You can see how the waveform grows and falls back to silenceduring the life of a note.I'll set a slower attack,(keyboard note)reduce the sustain level. At times I like to use delay calculators to find my attack and release times and compressors that allow you to set the attack and release in milliseconds, experimenting with different delay calculated times always seems to work. I have found this to work pretty well most of the time allowing me to quickly dialing in compressor settings!

Battaglia, Andy (18 September 2007). Retrieved 3 May 2018. Strew, Roque (12 September 2007). Archived from on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2018. Greenblatt, Leah (7 September 2007).

Retrieved 3 May 2018. Macpherson, Alex (15 June 2007). Retrieved 3 May 2018. Simpson, Claire (18 June 2007). Retrieved 3 May 2018. Naylor, Tony (18 June 2007).

Archived from on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2012. Harvell, Jess (21 June 2007). Retrieved 19 February 2012. Reeves, Mosi (October 2007). 23 (10): 110–12.

Retrieved 3 May 2018.

By Eddie BazilWhether you're programming electronic beats, or reinforcing rock drums, there's more to drum layering than meets the ear.We engineers and producers have been layering all manner of sounds since the early days of levered mixers and analogue tape the width of a small estate car. Drums, vocals, guitar lines, synths, basses.

The list goes on: they've all been placed under the 'layering hammer' over the years. While the basic concept may remain the same as ever, the techniques, and the quality of result that everyone expects to hear, have evolved considerably — it's no longer a simple matter of slapping one sound on top of another, because we've grown accustomed to good results and we can hear sloppiness.' But why layer drum samples at all,” I hear you cry, 'when I can easily find the sample I need?” I might be forgiven for agreeing with you. After all, what's the point of rolling your own when people like me pour years of experience and skill into creating sample libraries that do the job for you? Ready-made samples can be exactly what you want, but more often than not they merely come close — and why settle for close when you can achieve precisely what you desire? Even if you use commercial samples as a starting point, it's helpful to know how you can manipulate them to achieve your aims. One question that often arises is whether the composite sample you're creating should be saved as a mono or a stereo file.

The answer, of course, is 'it depends.” Personally, I tend to work in stereo right until the end of the process, as this allows me to use whatever processing I want without the worry of compatibility. Only when I've finished sculpting the sound will I decide whether to keep the result as a stereo or mono file, or both.There's usually no problem bouncing in stereo, but mono samples might suffer from phase cancellation, particularly where you've used certain stereo widening processes. On the other hand, mono samples take up half the space, which can eventually be beneficial in a vast library; and there's nothing to be gained bouncing to stereo if all the layers and processing are mono.

(You can, of course, add stereo interest to such samples in the mix, with send effects or mono-to-stereo insert effects.). In the main text, I suggest using your DAW to balance, nudge and combine different sample layers to create your new sound, because it's such an easy way to work. But you need to be aware that inserting plug-ins on any individual layer can result in phase carnage! EQ, by its very nature, uses filters, which can be shaped to taste within the limits of the equaliser. Whether boosting or cutting, you need to be wary of phase shifts. For this reason, I recommend using linear-phase EQs, which impart no phase shifts when boosting or cutting. Start with the usual players: low-pass, high-pass and band-pass filters, and a gentle slope of 6dB/octave, and go from there.

Register Your Bike. Get the latest news on Raleigh USA racing, bikes and offers! Phone Number Date of Birth (MM/DD/YYYY) Marital Status Are there any. Please enter a number between 0 and 7. Multisport Competition. Reg number raleight bikes. Raleigh Bicycle Registration Registering your bike with us serves as proof of ownership for any future warranty issues, and provides a record of the serial number in case your bike is ever lost or stolen.

Try to avoid using very narrow Q settings, as these can lead to harsh resonance, which will wreak havoc in this context. Play it safe and start with a Q factor of one or less. This means you have a wider bandwidth control when cutting or boosting. At the end of the day we're trying to hear, and utilise, the results of the phase-cancelled content, and any form of frequency altering tools will have a distinct impact on the sound. But this doesn't mean you have to be timid. Far from it: start meekly to avoid mistakes, and work from there — once you have control, you can take it as far as you want.

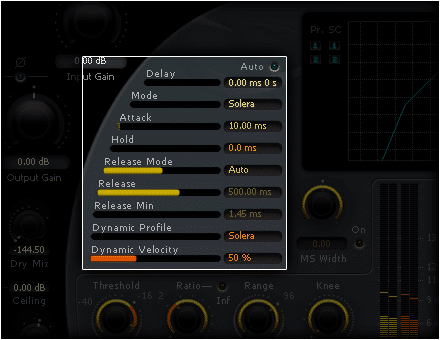

A typical folder structure example from the author's sample library.Drum layering means searching through vast libraries of samples to find your raw materials, and you'll want to do that quickly — so the sooner you realise the need for some form of structure in your library, the easier and more productive your life will become. At first, it may seem that there's no need for any specific format or directory listings, as the sample count is small and will fit into a 'drums' directory, but I guarantee that as time moves on your library will expand, so you need to plan ahead.Folder Structures: Creating folders for the key drum elements is a good and obvious start: give kicks, hi-hats and snares their own folders, and at the very least you'll have the basis to develop a hierarchy of folders with more specific categories. Your 'kicks' folder might have subfolders called 'Acoustic Kicks', 'Synthetic Kicks', 'Sampled Kicks' and so on. The same approach can be applied to all drum elements. When dealing with drum layering projects, you need to take this methodology much further, categorising the sounds by various different characteristics.One of the most important things in shaping a composite drum sound is your ability to control its dynamic envelope, by tweaking the Attack, Decay, Sustain and Release of individual layers. These parameters can be used to refine the structure of your library. For my own work, I tend to have subfolders that house each of these elements (A,D,S and R), and it really does make for much easier mixing and matching of sounds.

You can see what I mean from the screen in this box.Creating similar parallel folders with their own subfolders is a great way to build on this. For instance, I have a folder called 'Effected Drums', which houses drum sounds that I've run through processors and effects.

This allows me to keep the dry sounds away from the wet sounds, again giving me speedy access to what I want. In that folder, I'll have subfolders for different effects and sounds. You can add as many subfolders as you want: I'll keep adding and adding, without placing restrictions on myself.Label-conscious: Your library will expand quickly in this way, and you need to think hard about the names you use for both your folders and your samples. At the very least, it helps to keep the terminology simple and accurate, but after a while, it can become incredibly hard to think up appropriate names without being repetitive (which can be a really soul-destroying feeling!). You need a system.You could start names with a prefix, based on the sample source: if the sample was taken from recorded material this might be the artist name, and/or the track name; or if a drum sound was from a specific kit or drum machine, you could name it accordingly (for example, 808 bass drum tone).

Continuing with the last example, you could name further 808 drum sounds based on their duration, frequency, key location and so on. You'll probably end up with hundreds of names starting with '808 Bass drum tone', but this approach of creating directories with prefixes for genre, type, duration and so on is the method I always adopt nowadays, because it makes the whole layering process more manageable. If you're after 'slamming' loudness from your new sample, use a limiter or compressor on the master bus or the channel group, much as you might use a mix-bus compressor, as this will allow all the layers to be processed simultaneously. This is also often done when trying to 'glue' sounds together. However, make sure that you do this from the outset, so that the phase relationships between layers remain consistent. If you want to shape the sound of individual layers, instead use dynamics on individual channels instead — but do be wary of the effect this will have on the phase values of the layer, and thus the way it combines with the other layers. All contents copyright © SOS Publications Group and/or its licensors, 1985-2019.

Audio Processing Attack Delay Sustain Release Video

All rights reserved.The contents of this article are subject to worldwide copyright protection and reproduction in whole or part, whether mechanical or electronic, is expressly forbidden without the prior written consent of the Publishers. Great care has been taken to ensure accuracy in the preparation of this article but neither Sound On Sound Limited nor the publishers can be held responsible for its contents. The views expressed are those of the contributors and not necessarily those of the publishers.Web site designed & maintained by PB Associates & SOS.